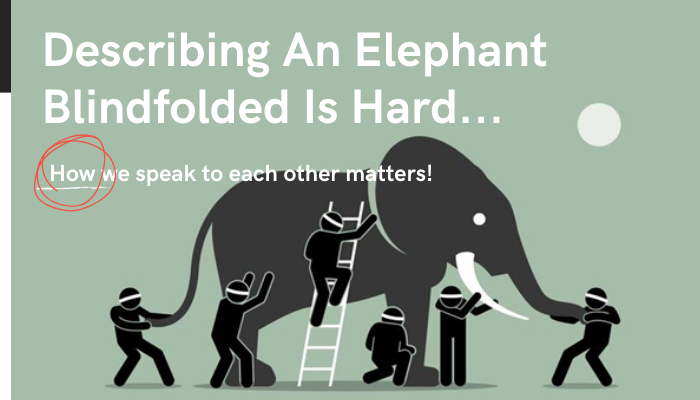

Take three people that have never seen an elephant, blindfold them, and set them a task to describe it by touch alone. What do you think would happen?

Scenario 1

The first person reaches out and touches the elephant’s trunk. What they feel is a long, dexterous, and smooth object. The first person puts their observations together in their head and exclaims “Ah-ha, an elephant is like a snake!”.

The second person reaches out and feels a tusk. The second person cries out “What? No, it’s not!”. In their mind what they felt was long, solid, and pointed. “I don’t know why you think this is like a snake. It’s more like a sabretooth tiger than anything!’.

The third person reaches out and feels a portion of large, leathery skin and cries out “What are you talking about!?” To them, the elephant is solid and feels like leather. “You’re both wrong! An elephant is like a Rhino!”

The three are led away and asked to conclude as a team what the elephant looks like. They argue and fight and come to no conclusions. Their observations are too disparate for compromise.

All three people are technically correct. A trunk is snake-like, a tusk would imply a sabretooth-like form, and elephant skin is rhino-like. However, without further context, none of those observations make sense when combined with each other. A snake, sabretooth tiger, and rhinoceros are too contextually different to make sense from three individual perceptions.

What’s wrong here?

When everyone believes their observation to be factual, and in contradiction to other observations, conflict naturally arises. Each person knows what they felt, and they ‘know’ their deductions are accurate, therefore the others must be wrong.

I see this scenario play out a lot in the start-up world. It’s completely natural for teams to conflict in such a way when trying to piece together a complicated reality with individual perceptions and assertions alone. The problem is, however, that consensus will never be reached if this approach is taken within any team, irrespective of how ‘correct’ everyone is with their observations.

What about this scenario?

We inform the blindfolded people that everything they observe needs to be communicated as an opinion, which is to be composed of the facts (as they observe them) and any assumptions they are making. The opinion is to be framed in a way that clearly articulates what assumptions are being made and what facts are being relied upon to form the opinion.

Person one reframes their statement. “The facts as I see them are that I have felt a long, thick, dexterous appendage. I’m assuming that this is the complete form of the elephant as I have no other information to contradict this. Therefore, my opinion is that the elephant has the form of a snake’.

Here person one has done three things. They have outlined the facts as they see them in the form of detailed observations. They have then outlined what assumptions they are making and why. They have then framed their opinion based on the combination of assumptions and facts, as they see them. It’s now completely clear to everyone what the facts, assumptions, and opinions being made by person one are and now they can be discussed and debated in a meaningful way.

Person two then responds. “The facts as I see them are that I have felt a long, solid, non-dexterous, pointy object. I’m making the assumption that this can’t be the complete form of the elephant as it doesn’t seem to be a living object, but I have no other information to confirm this yet. My opinion is that this object is a tusk and that the elephant, therefore, must have the form of a sabretooth tiger, as this is the closest form that I’m aware of that has a tusk.

Here person two has also outlined the facts as they see them in the form of detailed observations. They have then outlined what assumptions they are making and why. They have then framed their opinion based on the combination of assumptions and facts, as they see them. It’s completely clear to everyone what the facts, assumptions, and opinions being made by person two are, and now they can be discussed and debated in a meaningful way.

If person three were then to make their statement in the same way, the team can now pull together and constructively discuss and debate.

Any assumptions being made can be contested. Person three can say “person two, you assumed that sabretooth tigers are the only animals that have tusks. I challenge that assumption. What about a woolly mammoth? They have tusks too.” “Great point, I hadn’t thought of that!”.

Person two might then say to person one “person one, the facts you have given are clear, but you’re assuming that this is the complete form of the elephant. If we were to assume that what you felt isn’t the complete form, then, based on our observations, what you felt could be a trunk. What do you think? Would that change your opinion? “Yes, it would!”.

Person three could then say “What I felt definitely wasn’t woolly like a mammoth, so we need to put this all together. We could have something that feels like a rhino, with large tusks and a trunk? Do we all think that an elephant might be a smooth, Rhino like mammoth?” That’s pretty close!

What’s the difference?

As contrived as the language in this example might seem, framing our opinions as a combination of our perceived assumptions and facts is one of the most effective communication techniques for teams trying to solve complicated problems.

By understanding that the composition of any opinion is a combination of a series of facts and assumptions, as perceived by an individual, on a specific statement or topic, then we can debate these component facts on their merits whilst also removing the personal association tied to the opinion.

This wasn’t done well in our first scenario and is why we see the protective behaviours from our teams when first debating the form of the elephant.

In the second scenario, by articulating and framing their opinions in a way that outlines their composition, the team was able to focus the debate on the facts and assumptions that made up the individual opinions. This made the team more effective and lead to them forming a consensus.

This communication model is incredibly useful for resolving conflict. When opinions are deliberately structured as the combination of an individual’s assumptions and perceived facts it allows for depersonalised and constructive debate on the fabric of the opinion. It opens people up to be more amenable to having their opinions challenged and it gives them the freedom to change their opinion when the underlying opinion compositions change.

So, next time your team is having trouble describing an elephant, give this communication technique a go and see if it helps bring all the pieces together.

About the author - Aidan Kenealy - Founder - Hole In One Ventures

Some people think operational efficiency is dull. But we think it's sexy – it leads to greater profitability and more enjoyment within your business. Read some hot topics in our performance articles.